[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Integration of Brain Research and Learning

A Brain Based Learning Approach Through Bonnie Terry Learning

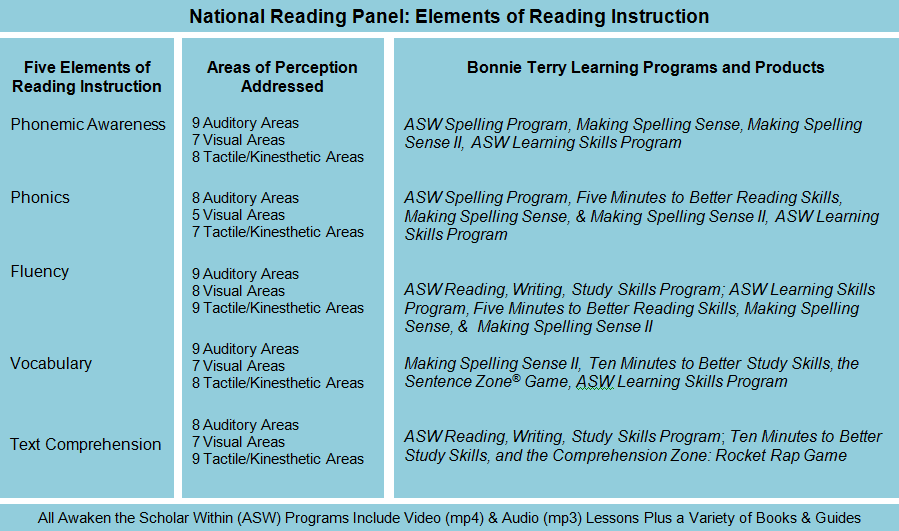

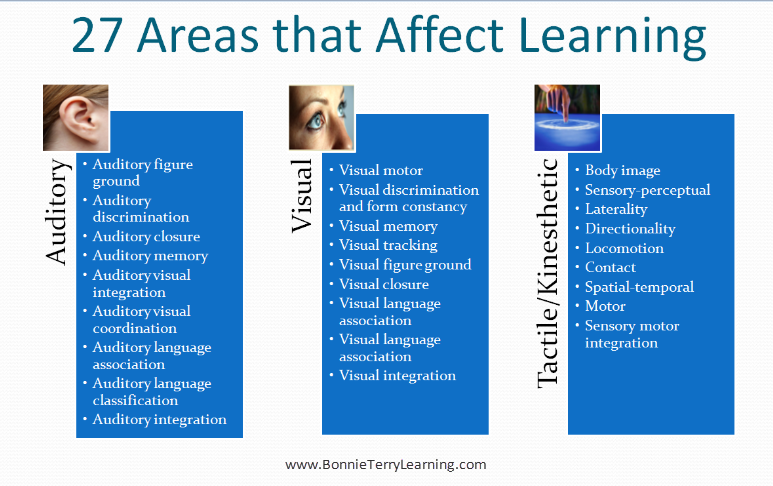

We all learn by hearing (auditory processing), seeing (visual processing), and doing (tactile/kinesthetic processing). Within each of those areas there are 9 sub-categories. When learning is difficult, it is due to one or more of those areas not working as efficient as they could, should and can.

Areas of Perception that Impact Learning

The Auditory Perception System

It is important to remember that hearing is not a based on only one sensory-perceptual skill. The central auditory nervous system (CANS) is a complex system with multiple components (sub-categories) and levels. Anatomically, the auditory system includes nuclei and pathways in the brainstem, subcortex, primary and association areas of the cortex and corpus collosum. Much of what constitutes central auditory processing is pre-conscious. That is, it occurs before a listener’s conscious awareness. What is experienced by the listener is an auditory perceptual event (Plomp, 1976; Tyler, 1992; Warren, 1984).

It is important to remember that hearing is not a based on only one sensory-perceptual skill. The central auditory nervous system (CANS) is a complex system with multiple components (sub-categories) and levels. Anatomically, the auditory system includes nuclei and pathways in the brainstem, subcortex, primary and association areas of the cortex and corpus collosum. Much of what constitutes central auditory processing is pre-conscious. That is, it occurs before a listener’s conscious awareness. What is experienced by the listener is an auditory perceptual event (Plomp, 1976; Tyler, 1992; Warren, 1984).

Although the CANS is critical to auditory functions, including spoken language processing and many other complex signals, several other factors are involved as well. Even the simplest auditory tasks are influenced by such higher-level, nonmodality-specific factors as attention, learning, motivation, memory, and decision processes. Higher level contextual information influences the perceptual analysis of the acoustic signal, and various knowledge sources interact and support the auditory processing of spoken language and other complex acoustic signals, such as music (Bregman, 1990; Duetch, 1975, 1982; Handel, 1984, 1989; Jones, 1987; McAdams & Bregman, 1979; McAdams & Saariaho, 1985).

Sample of Therapeutic Activities That Address Auditory Processing

Activities/Resources that teach synthesis of phonemes into words…

The spelling lessons in Bonnie Terry Learning’s (BTL) ASW Spelling Program, Making Spelling Sense, and Making Spelling Sense II use a method that teaches both this process and the structure of the language. Each lesson teaches both the spelling patterns and the words, one letter or blended letters at a time, and the student then blends all of the letters together to form words.

The (BTL) ASW Learning Skills Program, ASW Reading, Writing, & Study Skills Program, and Five Minutes to Better Reading Skills all teach syllable segmentation, segmentation of individual phonemes, blending, and fluency.

The ASW Learning Skills Program teaches all nine areas of auditory perception, the nine areas of visual processing and the nine areas of tactile/kinesthetic processing. This includes the above steps.

The Visual Perception System

Early Choice Pediatric Therapy has found that once a child enters school, about 75% of the classroom activities are directed through visual pathways. The majority of students who have problems with their vision system, upwards of 90%, are never diagnosed.

Early Choice Pediatric Therapy has found that once a child enters school, about 75% of the classroom activities are directed through visual pathways. The majority of students who have problems with their vision system, upwards of 90%, are never diagnosed.

According to the National Vision Research Institute of Australia, about 40% of the human brain is involved in one form or another with visual processing. Upon visual input, visual signals leave the eye and follow a path into the superior colliculus in the brainstem, where the electrical impulses react and control all eye movements such as blinking, dilating pupils, and tracking objects that are moving or tracking a line of words. The optic nerve then forms synapses and sends neurons to the occipital lobe of the cerebral cortex. This pathway is responsible for experiencing and controlling visual perception. The input comes from both eyes, the right cortex receiving impulses from the left orbit and the left cortex receiving input from the right orbit.

Once the input reaches the cortex, it must be processed with the neural networks. Non-verbal visual information and verbal information both need to be processed. This includes orthographic information. Patterns need to be distinguished.

Multiple processes of the vision system work together for visual perception and discrimination of orthography and output (George McClosky, Ph.D, 2007). The sound-symbol connection is extremely important for successful reading. According to Berninger and Richards, sound codes in speech play an important, even fundamental role in the recoding of visual stimuli into language using the orthographic word form representations.

Additionally, executive function does play a part in this process, as well as visual, auditory, and muscle memory. Background knowledge of both general and specific nature in both content and language goes hand-in-hand with reading and gaining meaning from what one reads (comprehension). The ability to decode and encode words that are familiar, unfamiliar, or nonsense words and filter and sort them into usable meaning brings comprehension.

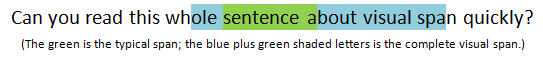

It is also important to note that Rayner, in 1997, summarized 25 years of research on eye movements. Reading obviously involves eye movements, which are called saccades, when the eyes are moving rapidly. The rapid eye movements and tracking are separated by fixations when the eyes are relatively still. Saccade movements typically travel about 6 to 9 letter spaces; they are not impacted by the size of print. The complete perceptual span is larger, extending to 14 or 15 letter spaces to the right and 3 to 4 spaces to the left. It is the saccade movement to the left combined with the perceptual span length that assures that every letter of every word enters the visual field.

Understanding this visual span perception span combination leads us to realize that efficient readers do this easily. About 10-15% of the time, readers also shift back (known as regression) to look back at material that has already been read. And as text becomes more difficult, saccade length tends to decrease and regression frequency increases.

It is important to note that the space between words does facilitate fluent reading. When spacing between words varies or is not available, reading is slowed by as much as 50%. The research further notes that efficient eye movement is more critical than generating predictions of upcoming words. Readers systematically move their eyes from left to right across the text and then fixate on most of the content words. The processing associated with each word is very rapid, and the link between the eyes and the mind is very tight. Rayner, K. (1997) Scientific Studies of Reading, 1(4) pages 317-339.

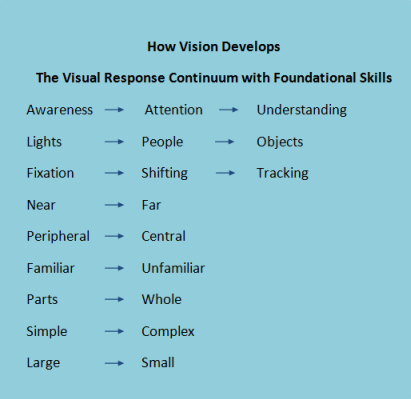

Vision develops in an orderly manner and improves over time. Each principle or skill has a continuum. Additionally, each has a range of responses from very basic to complex. A child can respond at any point on each skill continuum and can be at different points at any given time on each continuum.

Sample of Activities/Resources That Address Visual Processing

- Visually tracking objects without moving the head.

- Catching objects in space, e.g. bean bags or balls.

- Coloring “in the lines,” copying activities.

- Visual tracking of letters or words with a built in scoring (accountability) system.

- Visual memory activities

- Visual discrimination activities

- Eye-aiming activities

- Visual figure ground activities like hidden pictures

- Visual language activities that build vocabulary

- Play marbles, jacks, and other eye hand skill games

- The BTL ASW Learning Skills Program, which addresses all 9 areas of visual processing

- The BTL ASW Reading, Writing, Study Skills Program, which addresses 7 areas of visual processing

- The BTL Five Minutes to Better Reading Skills reading fluency program, which addresses 5 areas of visual processing

The Tactile/Kinesthetic Perception System

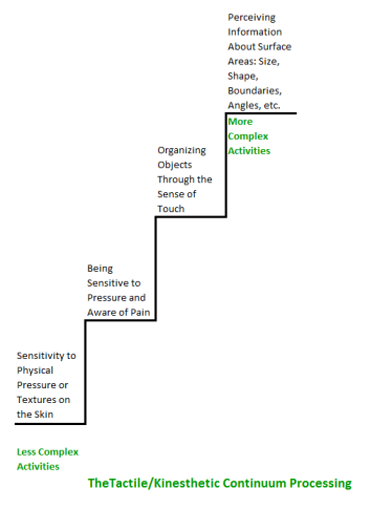

In the tactile/kinesthetic processing system, otherwise known as the haptic processing system, information comes in from either tactile (touch) or kinesthetic (movement). Difficulties or dysfunctions in this system result in problems performing motor tasks such as writing, note-taking, manipulating buttons or tools and equipment. Often, difficulty also arises with learning motor performance skills (Gibson, 1965).

In the tactile/kinesthetic processing system, otherwise known as the haptic processing system, information comes in from either tactile (touch) or kinesthetic (movement). Difficulties or dysfunctions in this system result in problems performing motor tasks such as writing, note-taking, manipulating buttons or tools and equipment. Often, difficulty also arises with learning motor performance skills (Gibson, 1965).

There is evidence that children with moderate learning disorders often have poorly functioning visual, auditory, or vestibular (balance) systems which can contribute to their lack of attention, task avoidance, behavior issues, and self-regulation (Wilson & Heiniger-White, 2008).

This is important, because vestibular deficits affect every facet of child’s being, including: health, ability to learn, and overall academic achievement (Mehta & Stakiw, 2004). Children with vestibular function disorders often need additional help with learning, due to various contributing factors: impaired spatial orientation, memorization task difficulties, balance problems affecting their ability to sit upright in their chairs, and unstable neck muscles that create fatigue posture at the desk. Young children frequently cannot describe vestibular symptoms, and teachers frequently lack of awareness of vestibular problems, lead to both misdiagnosis or under-diagnosis of this condition (Mehta & Stakiw, 2004).

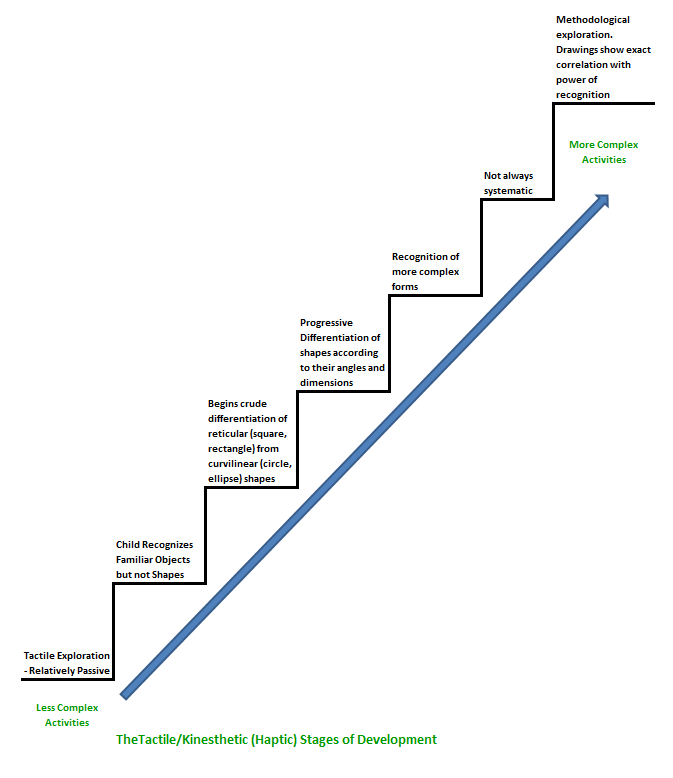

For a better understanding of the developmental stages see the following chart.

Input for the tactile/kinesthetic system comes from the stimulation of the mechanoreceptors in skin, muscles, tendons, joints, as well as the vestibular system. Gibson and Revesz note that the haptic input is generated by manually exploring objects in space. The fundamental characteristic of the tactile/kinesthetic system is that it depends on some sort of contact. The skin needs to be in contact with an external surface or encountered through a glove or a shoe. The Haptic system directly impacts learning areas critical to learning and reading, encompassing spatial awareness, laterality, directionality, locomotion, contact, and sensory motor integration.

This system directly impacts the formation of letters, the ability to see letters correctly, the understanding of sizes, shapes, writing, and the physical response. The Haptic system is directly involved with sorting and classifying, skills which improve language and comprehension skills.

Dr. Franck Rasmus in 2003 states “Dyslexia research is now facing an intriguing paradox: it is becoming increasingly clear that a significant proportion of dyslexics present sensory and motor deficits.” An additional summary states the three leading theories of developmental dyslexia: (i) the phonological theory, (ii) the magnocellular (auditory and visual) theory and (iii) the cerebellar theory. Results suggest that a phonological deficit can appear in the absence of any other sensory or motor disorder and is sufficient to cause a literacy impairment. Auditory disorders, when present, aggravate the phonological deficit, hence the literacy impairment. However, auditory deficits cannot be characterized simply as rapid auditory processing problems, as would be predicted by the magnocellular theory. Nor are they restricted to speech. Contrary to the cerebellar theory, we find little support for the notion that motor impairments, when found, have a cerebellar origin or reflect an automaticity deficit. Overall, the present data support the phonological theory of dyslexia, while acknowledging the presence of additional sensory and motor disorders in certain individuals.”

Wilson and McKenzie, 1998, summarized that the greatest deficiency with children with developmental coordination disorder is in the visual-spatial processing areas. Findings of 50 studies show that perceptual problems, especially in the visual modality, are associated with difficulties or problems in motor coordination. Therefore, activities that give direct explicit instruction in the tactile kinesthetic system areas are indicated.

Sample of Activities/Resources That Address Haptic (Tactile/Kinesthetic) Processing

- Matching activities

- Balance beam activities

- Bean bag activities

- Drawing

- Painting

- Word searches

- The (Bonnie Terry Learning) BTL ASW Learning Skills Program

- The BTL ASW Spelling Program

- The BTL ASW Reading, Writing, and Study Skills Program

- BTL Games: the Sentence Zone game, the Comprehension Zone Game, and the Math Zone

Conclusions:

Comprehending and using spoken language and written language (reading) does depend on the initial detection of sensory input (VAKT) and perceptual analysis of the auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and tactile input to the central nervous system. Researchers (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1994) have found that training children needs to be more explicit and intense for at-risk students than for those who do not struggle if the training is to be effective for those with reading disabilities.

Furthermore, intensive and strategic instruction in segmenting and blending at the phoneme level is warranted (e.g., Snider, 1995). Further research by Chard and Osborn, 1998, states that specific principles need to be in place with instruction to be effective.

The first step to start with is the sound symbol relationship, model from larger units (words and rhyme) to smaller units, which are the individual phonemes. Then, move from the easier tasks of rhyming to the more complex tasks of blending and segmenting.

It is critical to use additional activities and strategies to facilitate the manipulation of sounds and print (reading material) and writing. Additionally, the automaticity of the phonological processes is important in all of three learning areas: auditory, visual, and tactile/kinesthetic. And, within this automaticity we need to keep in mind that each of the 5 steps of the reading process is impacted by multiple of the 27 areas of perception. When those areas are addressed with specific skill instruction, reading and learning skills improve quickly.

A variety of activities that comprehensively address skills through auditory, visual and tactile/kinesthetic modes of learning is critical to improving auditory processing, visual processing, and tactile/kinesthetic processing, ultimately improving all learning and reading skills.

Additional Studies Regarding the Methods Used In Bonnie Terry Learning Products

Eric Jensen, author of Brain Based Learning, (1997) states that up to 87% of students do NOT learn from hearing alone. He goes on to state that we under-utilize our visual system when learning. Use of colored handouts, charts, graphs, photographs, posters, and graphic organizers such as those incorporated into Bonnie Terry Learning products will increase student’s learning through boosting and strengthening use of the visual system. Using visual and kinesthetic methods increases student performance and decreases discipline problems.

Research by Robert Sapolsky (1996, 1999) relates stress to learning. A student under stress or distress will have a much more difficult time retaining information.

Read more on brain based learning and brain studies here.

Strategic Instruction Model

The Center for Research on Learning based at the University of Kansas has been studying the best ways to help promote effective teaching for over 30 years. It has developed numerous strategies incorporated into an overall program called the Strategic Instruction Model (SIM Strategies). In essence, the Strategic Instruction Model aims to promote effective teaching and learning of critical content in schools. SIM strives to help teachers make decisions about what is of greatest importance, what we can teach students to help them to learn, and how to teach them well.

The Center for Research on Learning developed specific learning strategies for assisting students to understand information and solve problems. A learning strategy is a person’s approach to learning and using information. Students who do not know or use good learning strategies often learn passively and ultimately fail in school. Learning strategy instruction focuses on making students more active learners by teaching them how to learn and how to use what they have learned to problem solve, comprehend better, write better, and be successful.

See more about reading strategies, language (sentence building), and comprehension games supported by the Strategic Instruction Model research.

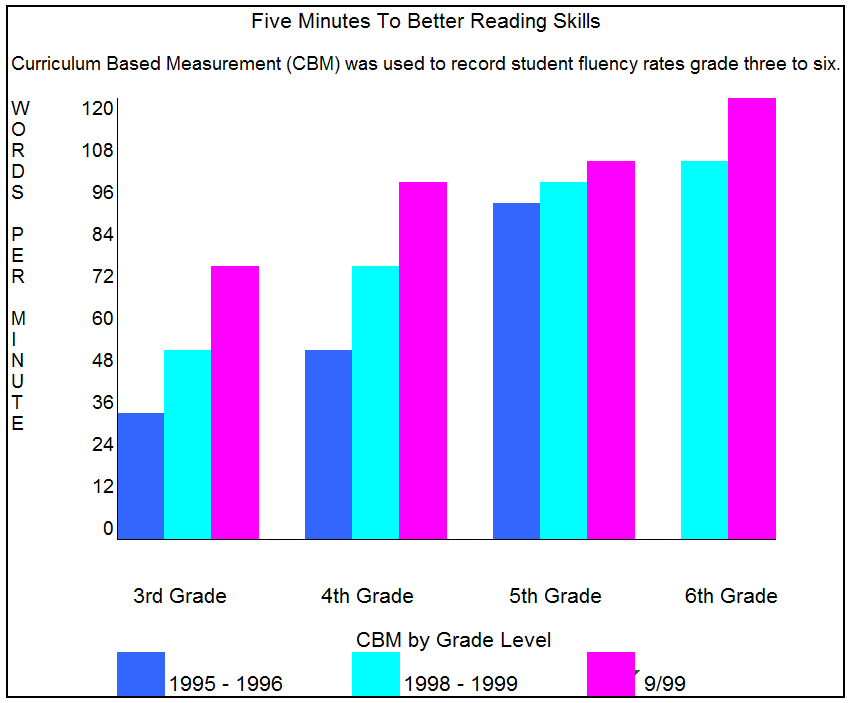

5-Year Independent Study Using Five Minutes to Better Reading Skills

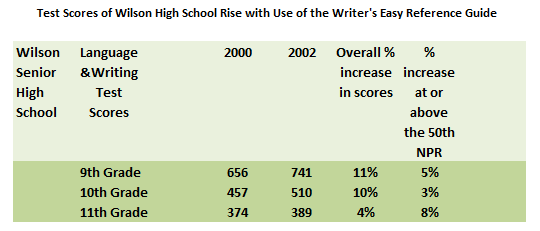

Woodrow Wilson Senior High’s Language Scores, LA Unified School District, have increased 11% each year since they have implemented the Writer’s Easy Reference guide into their school.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Research Behind Bonnie Terry Learning Programs and Products

Bonnie Terry Learning and Orton-Gillingham A Comparison

Brain Research – How Bonnie Terry Learning Programs and Products Work

Reviews and Scope of Programs and Products

Testimonials and Reviews[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator][vc_column_text]Bonnie Terry, M. Ed., BCET

Phone: 530-888-7160

Blog: Reading, Writing & Math Help for Dyslexia, LD & ADHD

Best Selling Author: Family Strategies for ADHD Kids, School Strategies for ADHD Kids, Five Minutes to Better Reading Skills Best selling co-author: Amazing Grades

Radio Program: Learning Made Easy Talk Radio every Monday 11:00 a.m. CT & 5:00 p.m. CT on AWOP[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]